- John West

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/25/2015

- Posts: 1,254

Problems for Presentism

"The now that passes produces time,

the now that remains produces eternity."

Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy.

I think presentism has more problems than people typically realize.

For one, it seems unable to account for past tense truthmakers. It at least seems that more than one possible past could have led to the present state of the world. An explosion, for example, could have been caused by a lightning strike, or by a chemical leakage, or by an electrical short-circuit, or any number of other ways. If it's possible that more than one past could have led to the present state of the world, then the totality of present states-of-affairs cannot serve as truthmakers for a determinate past. Hence, the totality of the present state-of-affairs cannot serve as truthmakers for a determinate past.

And what would the duration of “now” be for presentists? Is the present moment a second? Is it a year? Is it an hour? How do we choose one over the other? Is it “Now in the Year of the Lord 2015”, or “Now while I rest”? “Now in the 21st century”, or “Now, now, very now, an old black ram is tupping your white ewe”?[1] How long is “now”? It seems presentists' only non-arbitrary option is to admit a smallest possible unit of time. If, however, time is continuous, then there is no smallest possible unit of time. Hence, admitting a smallest possible unit of time would commit presentists to the view that time is discrete.

But we don't experience time as discrete—everything seems to flow smoothly—and, I think, this should be an embarrassment for a view that prides itself on upholding our common sense intuitions.

Alternatives to presentism are the growing block theory, which preserves our experience of ongoing change, and eternalism, which helps with McTaggart's argument and the problem of God and future contingents.[2] Either alternative avoids both the above arguments.

[1]Shakespeare. Othello.

[2]I take it I don't need to talk anyone out of the view that only the future and present exist.

Last edited by John West (9/13/2015 8:13 pm)

- Scott

- Moderator

Offline

Offline

- From: Ohio, USA

- Registered: 6/26/2015

- Posts: 357

Re: Problems for Presentism

John West wrote:

I think presentism has more problems than people typically realize.

I think it has a further problem, which I describe in this short essay I wrote a couple of years ago. (It's available online, but I figured it was easier just to copy it here.)

N.B.: I'm somewhat less sympathetic to panpsychism than I was then (and even then I wouldn't have endorsed every conclusion that Sprigge wanted to draw from it). However, nothing in the point at issue requires that panpsychism be true; it's sufficient that there be such a thing as "experience" at all.

(And I'm not ruling out panpsychism either as long as it's not understood as a substitute for or alternative to classical theism. I've mentioned on Ed's blog a couple of times that I suspect there's a case to be made for identifying "prime matter" with "prime consciousness/awareness"; at the very least, there's a close analogy between prime matter's nonexistence apart from form and awareness's nonexistence without an object of awareness. Bill Vallicella has a little bit to say on the subject in one of his blog posts, but I'm not going to post a link; Google will do the job nicely for anyone who wants to read it.)

Anyway, on with the show:

A Short Argument for Eternalism

I present a very short argument that some version of eternalism must be true. The argument in brief is that temporal relations must be either real or unreal (that is, must either obtain or fail to obtain between moments of experience at different times); that if they are not real, then eternalism is trivially true; and that if they are real, then eternalism must be true in order for them to obtain.

By eternalism we shall mean here that there is some significant sense in which all of time exists tenselessly, timelessly, or eternally—that, in short, the more-or-less common-sensical view that the present moment winks into existence out of nothingness and then winks out again is false. As T.L.S. Sprigge notes in his essay “The Unreality of Time,” eternalism need not be taken to mean that time is literally unreal; it can be understood as a claim about what time is really like, i.e., the true nature of whatever it is in the real world that answers to the name of “time.” We are not concerned here with variants of the eternalist view, and our argument does not claim to tell us which version is the correct one.

Partly in order to avoid questions of relativistic physics and partly because I tend to agree with Sprigge that the noumenal reality behind the phenomenal physical world consists of innumerable finite centers of experience, I shall focus here specifically on moments of experience rather than events in physical spacetime.

Consider two such moments, for example my eating of a peanut butter sandwich for lunch yesterday and my recollection of that experience today. It seems unproblematic to say that the first moment of experience temporally precedes the second. There seems to be a real relation between the two such that the first comes before the second and the second comes after the first.

The question for the non-eternalist is whether that temporal relation really obtains. If “before” and “after” are not real relations, relations that in fact obtain between two objectively existing moments of consciousness, then it seems that time is unreal and eternalism follows trivially.

But if they do obtain, then the non-eternalist faces a worse difficulty. For if all that is ever real is the present moment, then there is never a time at which both moments of experience exist, and so at least one of the relata always fails to exist. Granting that my eating of the peanut butter sandwich yesterday does not exist now, if there is no sense in which it exists timelessly, then it simply isn’t “there” to be in a relation of “coming before” to the moment of my recollection. If past and present never coexist in any eternal sense whatsoever, then it should be simply meaningless to say that one comes “before” the other; the past simply fails to exist, and therefore can’t be “related” to anything.

A non-eternalist might reply to this argument by saying that the past does continue to exist, but only as past—that when the Moving Finger, having writ, moves on, each moment acquires a quality of “pastness” that differentiates it from the present moment without making it fall out of existence altogether.

I think this will not do, primarily for the reason Sprigge makes clear in his essay. My experience of eating a peanut butter sandwich has a certain quality of presentness that is simply part and parcel of the experience; without that quality the experience would not be what it is/was, and indeed would arguably not be an “experience” at all. (Sprigge’s own example, which has the advantage of great vividness, is a toothache.) If that moment of experience is not eternally “there” with that very quality of presentness, then it is no longer available as a temporal relatum, and when I say that the experience of eating the sandwich comes “before” my recollection of it, I am referring not to the experience itself (which no longer exists qua experience) but to its ghost. Surely this is not what we mean to say when we say one experience precedes another; the view that began by apparently cleaving to common sense in the end departs from it egregiously.

Unless some version of eternalism is true, then, we cannot even meaningfully say that one moment of experience precedes or follows another. That seems to be a pretty big problem for non-eternalists.

Last edited by Scott (9/13/2015 8:19 pm)

- DanielCC

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/26/2015

- Posts: 765

Re: Problems for Presentism

With regards to the second claim here a couple of potential responses one might give:

1. First of all one might argue that beings have Leibnizian essences and that these include the way said beings have come about e.g. this scorch-mark could only have come about as a result of that combustion (that’s an awkward example since it doesn’t involve two proper natural kinds but it will serve as an illustration – think Origins Essentialism).

2. With the risk of straying too far from the original challenge let’s look at in terms of the simple truthmaker problem for presentism vis what is it that makes past or future statements true?

Consider some event, say, Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. Might not the friend of Armstrongian ‘concrete states-of-affairs argue that the state-of-affairs 'God's-creating-the-world' (the term 'world' here is to be taken de re) includes the state-of-affairs God’s-creating-[whatever the present tense truthmaker for Napoleon’s-retreat-from-Moscow is] and thus serves as a truthmaker for that proposition? The act of creation is from eternity so said state-of-affairs also holds from eternity.

Last edited by DanielCC (9/13/2015 7:59 pm)

- John West

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/25/2015

- Posts: 1,254

Re: Problems for Presentism

DanielCC wrote:

2. With the risk of straying too far from the original challenge let’s look at in terms of the simple truthmaker problem for presentism vis what is it that makes past or future statements true?

Consider some event, say, Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. Might not the friend of Armstrongian ‘concrete states-of-affairs argue that the state-of-affairs 'God's-creating-the-world' (the term 'world' here is to be taken de re) includes the state-of-affairs God’s-creating-[whatever the present tense truthmaker for Napoleon’s-retreat-from-Moscow is] and thus serves as a truthmaker for that proposition? The act of creation is from eternity so said state-of-affairs also holds from eternity.

Suppose God had created differently. Would His Act of Creation have been different? If so, then God could have been different. If not, then God's Act of Creation can no more serve as the truthmaker for a determinate past than the present state of the world can.

- •

- Scott

- Moderator

Offline

Offline

- From: Ohio, USA

- Registered: 6/26/2015

- Posts: 357

Re: Problems for Presentism

John West wrote:

Suppose God had created differently. Would His Act of Creation have been different? If so, then God could have been different. If not, then God's Act of Creation can no more serve as the truthmaker for a determinate past than the present state of the world can.

Good point. And for classical theism, the second answer is the right one, since CT holds both that God is simple and immutable and that God's act of creation is identical with God (even if its "objects" might be, or have been, different).

Daniel's right, though, that an Armstrongian theist could take the approach he suggests; it's just that a classical theist would argue that it fails.

One possibly interesting question is why the classical theist would say it fails. Is it because the state of affairs God's creating the world is in some way unique among states of affairs, or is it because there's something fundamentally wrong with the whole "state-of-affairs" approach in general?

- John West

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/25/2015

- Posts: 1,254

Re: Problems for Presentism

Scott wrote:

John West wrote:

Suppose God had created differently. Would His Act of Creation have been different? If so, then God could have been different. If not, then God's Act of Creation can no more serve as the truthmaker for a determinate past than the present state of the world can.

Good point. And for classical theism, the second answer is the right one, since CT holds both that God is simple and immutable and that God's act of creation is identical with God (even if its "objects" might be, or have been, different).

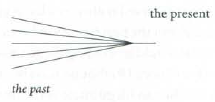

Right. It's a dilemma, but I wrote it figuring classical theists would have to choose the second half. Here's a diagram of the past as a set of possibilities that Robin Le Poidevin uses with the truthmaker argument:

The point is that the totality of present state-of-affairs is compatible with multiple incompatible pasts. As a result, the totality of the present state-of-affairs is an insufficient truthmaker for determinate statements about any one past.

The second half of my dilemma points out that if God's Act of Creation is also equally compatible with multiple pasts, then His Act of Creation is also insufficient. At least, it runs into the same problem as using the present state of the world.

- •

- John West

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/25/2015

- Posts: 1,254

Re: Problems for Presentism

Let us say a thin particular is a particular considered apart from its properties, and a thick particular is a particular taken together with its properties.

Scott wrote:

One possibly interesting question is why the classical theist would say it fails. Is it because the state of affairs God's creating the world is in some way unique among states of affairs, or is it because there's something fundamentally wrong with the whole "state-of-affairs" approach in general?

It's worth mentioning that the states-of-affairs view was, I think, most scholastics' view.

One reason I admit states-of-affairs is that I think they're required by the existence of Aristotelian universals and the need for truthmakers (ontological grounds of truths). What, for example, is the truthmaker of the statement “a is F”? It can't be a, if a is taken as a thin particular[1]. Since a and F could both exist without it being the case that a is F, the truthmaker for "a is F" also can't be the pair a and F. It seems a further entity is needed to make true the statement “a is F”, so I posit the state-of-affairs a's being F.

[1]If a is a thick particular, then it's a state-of-affairs by definition.

- •

- John West

- Administrator

Offline

Offline - Registered: 6/25/2015

- Posts: 1,254

Re: Problems for Presentism

DanielCC wrote:

Well that's the general problem of Divine freedom/Extrinsic Properties/Beliefs for Divine Simplicity isn't it? If the defender of simplicity must face that anyway.

I've already given my reply indirectly. For the reasons Scott mentions in the first paragraph of his reply to me, any classical theist is going to have to deny the first half of the dilemma, and thereby affirm the second half. I would go as far as to say that for classical theists affirming the second half of the dilemma—that God could have created differently without Himself being different—is just one of the goals of a solution to the problem.

Since I know I don't need to argue you out of theistic personalism (ie. The First Way), I won't.

- •

- Mark

- Member

Offline

Offline - Registered: 7/11/2015

- Posts: 33

Re: Problems for Presentism

John West wrote:

"The now that passes produces time,

the now that remains produces eternity."

Boethius. The Consolation of Philosophy.

I think presentism has more problems than people typically realize.

For one, it seems unable to account for past tense truthmakers. It at least seems that more than one possible past could have led to the present state of the world. An explosion, for example, could have been caused by a lightning strike, or by a chemical leakage, or by an electrical short-circuit, or any number of other ways. If it's possible that more than one past could have led to the present state of the world, then the totality of present states-of-affairs cannot serve as truthmakers for a determinate past. Hence, the totality of the present state-of-affairs cannot serve as truthmakers for a determinate past.

And what would the duration of “now” be for presentists? Is the present moment a second? Is it a year? Is it an hour? How do we choose one over the other? Is it “Now in the Year of the Lord 2015”, or “Now while I rest”? “Now in the 21st century”, or “Now, now, very now, an old black ram is tupping your white ewe”?[1] How long is “now”? It seems presentists' only non-arbitrary option is to admit a smallest possible unit of time. If, however, time is continuous, then there is no smallest possible unit of time. Hence, admitting a smallest possible unit of time would commit presentists to the view that time is discrete.

But we don't experience time as discrete—everything seems to flow smoothly—and, I think, this should be an embarrassment for a view that prides itself on upholding our common sense intuitions.

Alternatives to presentism are the growing block theory, which preserves our experience of ongoing change, and eternalism, which helps with McTaggart's argument and the problem of God and future contingents.[2] Either alternative avoids both the above arguments.

I know of at least some presentists (such as William Lane Craig) who would simply reject the idea of truth makers. He would ask something like "What makes a number part of reality, what makes 1+1=2 true?" It seems that though their is a kind of correspondence between realtiy and mathematics, there is no specific temporal object that we can point to that makes them true. So the requirement that there be presently existing truth makers would be, on his view, just misguided.

As for what constitutes the duration of the now, that seems a slightly muddled objection. "The Present" would just be whatever is real at a given moment, what we experience. When you ask how we can identify it, whether in seconds, weeks, years, or whatever, that's an epistemological question rather than a metaphysical/ontological one. The presentist feels no need to give an exact account of what measurement of time constitutes the present because our ability to identify it precisely doesn't effect the reality of the situation. There's perhaps a parallel here with the responses to some of Zeno's paradoxes.

Also, most presentists would that the attractiveness of their position is in large part due to the failure of others. Eternalism seems to give no explanation for the passing of time or why change is possible, for example.

1

1